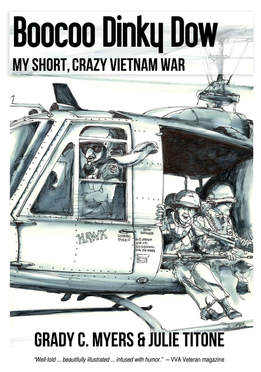

Jack Hawkins, aka "Hawk," at left with crew in 1969 Jack Hawkins, aka "Hawk," at left with crew in 1969 By Julie Titone Who, exactly, was Hawk, the helicopter pilot featured in Grady Myers's Boocoo Dinky Dow cover illustration and mentioned several times in his memoir? Grady never knew, and after he died in 2011 Hawk's real name remained a mystery to me. Now I know. And I know that the face Grady portrayed in the chopper window wasn't actually Hawk, who never wore a white scarf. Enlightenment came after I inquired of folks on a few Vietnam War-related Facebook pages if anyone knew Hawk. Within hours, I was on the phone with Jack Hawkins who had emailed me to say: "I was a 'slick' pilot in the 119th Assault Helicopter Company from August 1968 to August 1969. My nickname was Hawk. Time has erased a lot of memories, but I still remember some of the 'interesting' days. I am sorry to hear about Grady’s passing, as I would like to hear what he remembered during that period. The 119th was a good company and we always tried to give the guys on the ground the best support that we could." A slick pilot was a utility pilot -- someone assigned to provide transport of troops on and off the battlefields, and to bring in supplies and ammunition. In the picture shown here, Jack is at left. A handsome Texas Panhandle rancher, his weight was down some 20 pounds from the stress and exhaustion of the job. And he did see flying as his first real job -- the first one he was trained for. "I was in college and I was actually making the grades. But I knew the draft board was not going to let me go, and I always wanted to fly. So I enlisted to go to flight school." A year later, his boots were on the red soil of Vietnam. A really rough month Jack's photo shows him standing at his Huey with, from left, crew chief Robert Legasey and a 119th gunship pilot, Jim McDonald. Gunner John Morrison is in back, cleaning his M-16. The aviators are preparing to go into the Plei Trap Valley, where Grady was badly wounded in a firefight on March 5, 1969. Before he was rescued, Grady saw a Loach helicopter come into sight, then fly away. That might have been a 4th Infantry gunship, Jack said. In any event, from Grady's painful perspective, the cavalry had not yet arrived. "I am pretty sure that it was Ski that made the tactical emergency drop of ammunition that day when Grady was wounded," said Jack. "There was a heck of a firefight going on and they were running low on ammunition. Ski’s pilot was hit during that drop. Nilius, Hud, One-Cent, Clem, and others were also there for the guys on the ground. And the gunships that gave us cover so we had a chance to get in and out." "It took a team effort and I can’t emphasize enough that we were there for one another," he added. "The real warriors were the 18- and 19-year-old kids on the ground living in pure hell. God bless them." That was a really tough month for the 4th Infantry Division, Jack said. The worst came on March 30. "We had nine aircraft shot up. I think it was Alpha and Charlie company that we pulled out ... I didn’t see how we would come out of that alive." Jack's helicopter was never shot down, "and I never took that many rounds." He was grateful to sleep each night in a bunk, however short that slumber might be. There was no such luxury for the infantry. Life was especially hard for troops in the remote and mountainous Central Highlands. "Those poor guys, they went in two directions, straight up and straight down. We called them grunts," Jack told me. "Their tour on the ground there ... I don’t think anybody that had not done that could really understand." The best part of his job in Vietnam was transporting men out of that misery.  Coming out of it alive After his year in country, Jack went back to college and got a forestry degree. But he ended up spending his career flying helicopters for the petroleum industry. For the last 17 years before he retired, he managed helicopter transport for the National Science Foundation in Antarctica. Can you get further from Vietnam than that? Now living in a small Kansas town with his wife, Ann -- they married shortly after he left the Army -- Jack said he has no regrets about his service in Vietnam. "I never talked about it for years and years. Most people can’t really understand it. Then I started going to Vietnam Helicopters Pilots Association meetings. The first one I went to was in '85 or '86. We let our hair down a little bit. We still had hair then. That was a great healing process for me." Regarding hair ... Grady remembered Hawk as bald. A case of mistaken identity? "Major Carey, our company commander, flew with me a time or two as pilot and he was bald," said Jack, who had plenty of hair in 'Nam. "He was a good commander that all of us had a lot of respect for." Just as Grady portrayed it, the aircraft commander was piloting from the left, something unusual but done in the 119th because it provided better line of sight, Jack explained. Grady did take artistic license when he drew "Hawk" on the door. The white scarf? Two of the Loach gunship pilots wore scarves, according to Bob Robbins, who also served in Charlie Company and was there at Plei Trap. So, Grady's drawing represents a composite memory. It was Hawk's helicopter that flew Grady to his first combat assignment on a godforsaken hilltop. It was Hawk who Grady thought he saw circling overhead when he lay looking up through the trees, losing blood and hope. Many children of Vietnam veterans -- including the son Grady and I eventually had -- owe their existence to pilots like Jack Hawkins who ferried their fathers to safety. With special thanks to the folks at Vietnam War History Org, Vietnam War Book and Film Club and Vietnam Reflections Through Their Eyes

3 Comments

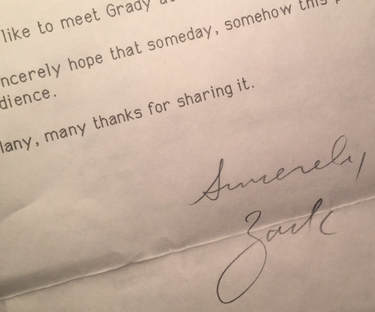

By Julie Titone In the 1990s, after Grady and I had produced a first draft of Boocoo Dinky Dow, I received the most wonderful letter from Zack, the talented husband of a journalist friend. When I'd learned he was a Vietnam vet who served in the 9th Infantry Division (Grady was in the 4th), I had sent him a manuscript. I was touched and encouraged by his response. Here is part of Zack's letter. "What I think is so important about what you've done is that you've made it possible for a person to tell his story who would otherwise never have told it. Most often, when a soldier tells a story about war, it's a soldier who is or will be a writer. For example, 'The Naked and the Dead' by Norman Mailer, 'Catch 22' by Joseph Heller, etc. Or it's a writer/reporter who, although not a soldier, is at the war in some capacity. Michael Herr, a reporter for Esquire, Rolling Stone and Ramparts, wrote 'Dispatches.' Hemingway wrote 'For Whom the Bell Tolls' after being in the Ambulance Corps. But it's unusual that an ordinary soldier who is not a writer can tell his own story. "I thought the ambush scene where Grady gets wounded was particularly good. What I most liked about it was there's no sense of orientation. It's an incredible kind of chaos -- which I think is very close to the truth. and some of the details -- the way Grady sees three little red marks suddenly appear on the back of the solder standing above him -- I don't think could be invented by the best writer in the world." Zack was never able to meet Grady, but told me how much he wished he could. Our readers regularly say that, and it's the highest compliment that "Boocoo Dinky Dow" receives. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed