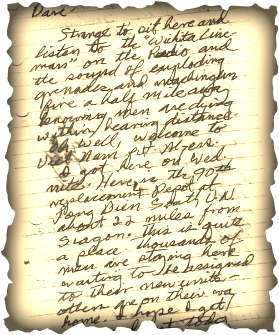

Strange to sit here and listen to the "Wichita Lineman" on the radio and the sound of exploding grenades and machine gun fire a half mile away, knowing men are dying within hearing distance. Oh, well. Welcome to Viet Nam Pvt. Myers. In the taped conversations that led to the memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War," Grady told me about his first days in-country. How he waited nervously at the replacement depot near Long Binh to learn what his assignment would be. But his anxiety became more vivid when I read his handwriting on pages torn from a skinny note pad. He was writing to his best buddy back in Boise, Dave Mueller. I was inspired to ask Dave for copies of the letters after watching the 1987 HBO documentary "Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam." In it, soldiers' words are brought to life by such actors as Willem Defoe, Robert DeNiro and Matt Dillon. Many are words Grady could have written: "Vietnam has my emotions in a seesaw. This country is so beautiful ... " "I do things to make them laugh. They call me dinky dow. That means crazy." "This was the first body I saw." The dramatic readings accompany some fascinating video, both news clips interspersed and home-movie-style footage taken by the G.I.s. In one clip, Gen. William Westmoreland talks to an M-60 gunner like Grady. In another, NBC reporter Sander Vanocur, sitting on sandbags at Cam Rahn Bay in 1965, reports on the "recognition that there will be no easy, painless or quick way out of this struggle." The letters and videos are interspersed with statistics, such as the average age of the Vietnam soldier. It was 19. Grady's age. In their letters, soldiers sometimes put an upbeat spin on things, or at least left out the worst of the experience. It's a testimonial to their friendship that Grady shared many emotions with Dave. On Fort Lewis stationery, he made it clear that training was miserable. "I'm sick of green -- that's all there is in this damned place." (Whether he meant the uniforms or the pine-studded and ever-soggy landscape is unclear.) But he added: "I'm going through this with some outstanding men, some I've already struck up good friendships with."  Grady Myers with a captured AK-47 Grady Myers with a captured AK-47 Always a big guy, he worried about his weight. He worried whether he'd be a good soldier. On the final flight into Vietnam, he wrote: "A few guys aboard are scared and some try to fend it off by being silly and making passes at the stewardesses -- which is fine with me 'cause I'm in on it too." He added that he was resigned to Vietnam and "going over there with a half-hearted spirit of adventure." Grady had talked about adventure as long as Dave had known him, since they met and bonded as newcomers to Borah High School. "We shared books about adventures we’d read. Now he was having his own. I remember being both scared for him and envying him for the camaraderie he had," says Dave, who describes his lifelong friend as someone whose compassionate, contemplative interior was masked by John Wayne swagger and humor. "There were deep philosophical thoughts going on inside that red-headed, fair-skinned noggin." In January 1969, after several weeks in Charlie Company, Grady wrote of feeling lost, overwhelmed and insecure. He was frustrated not to have any contact with the enemy. "We don't want any, but it seems to me, somehow, we're failing in our job, our duties." Contact came, of course. Grady's last letter to Dave was on American Red Cross stationery. "To make it simple," he began, "they shot me and I'm coming home."

3 Comments

This article first appeared in The Spokesman Review. By Julie Titone At the sight of me cradling an M-60 like the one he carried in Vietnam, Grady Myers would have rocked back on his heels and wiped tears of laughter from under his thick eyeglasses. Julie, complete with silver swoosh in her hair, was a 5-foot-3 machine gun granny. Hefting 23 pounds of firepower was one of many surprises I’ve had while sharing “Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War,” the story of Grady’s U.S. Army life in 1968-’69. He was a crackerjack storyteller who used artwork and humor to brighten a dark subject. I co-authored the memoir and published it in 2012, a year after his death. The machine gun episode took place after a book reading at the Veterans Memorial Museum in Chehalis, Wash. Despite my uneasiness with firearms, I had been curious about the M-60, which soldiers called the pig. It’s what Grady humped through the tropical heat and up the mountainsides, what he was firing in the ambush that he barely survived. So when museum staff asked if I’d like to hold one, curiosity won out over discomfort. Good stories like Grady’s are timeless. Still, it can be a challenge to interest people in a book about a war that many don’t remember and others want to forget. One way I do that is to ask if there are any veterans in the family. One 50-something bookstore customer furrowed her brow and answered, “No.” Then her son reminded her that Uncle Bob served in Vietnam. “Oh, that’s right,” she said. “But he never talked about it.” I’ve met a lot of Uncle Bobs lately. Many have opened up about their war experiences after reading “Boocoo Dinky Dow.” Often a veteran’s first response to the book is a cheerful recognition of the title. “Dinky dow! I haven’t heard that in 40 years!” It is how American soldiers heard the French/Vietnamese phrase beaucoup dien cai dau, meaning very crazy. Vets regularly chide me for using the Urban Dictionary spelling of the slang expression. It should, they insist, be bookoo, or bucu. One gave me a lapel pin that reads “Dinky dau.” I was unprepared for my emotional connection to the scores of combat veterans I’ve met. The vets who chat with me after book readings. Who visit my living room. Who post comments on the “Boocoo Dinky Dow” Facebook page. How else to put this? I love these guys. Another surprise: the depth of readers’ curiosity about my relationship with Grady. Why, people wonder, would a woman put so much effort into sharing her ex-husband’s story with the world? I tell them that a writer can’t let a good story go to waste—certainly not a story about a gentle, nearsighted teenager who is transformed into a machine gunner nicknamed Hoss and thrust into an insane conflict on the other side of the world. My biggest motivation was to honor Grady. Even though we divorced long before he died, he remained a friend. (One of his platoon mates responded to this information by saying, “Well, that’s refreshing!”) Body counts, Agent Orange, Zippo raids, napalm, post-traumatic stress and political gamesmanship. All were signatures of the Vietnam “police action” (never officially a war), and I’ve learned a lot more about them in the last year. I’ve seen battlefield photos I’d like to banish from my brain. What I am happy to remember are the many personal stories I’ve gotten in return for sharing Grady’s. They’re like pieces of a puzzle. Put together, they create a picture of war’s trajectory and of its impact on our national psyche. I could fill another book with these stories. That unusually cheerful professor I know? Turns out he’d been a soldier who, after zipping so many buddies into body bags, came home determined to savor each day. Another veteran calls Vietnam the best thing that could have happened to him, because it kept him out of the family business, which was the Mafia. One fellow remembers strangers who, upon seeing his uniform, bought him drinks and meals. Another insists he was spat upon by war protesters. A former protester, still a peace activist, winces at the memory of menacing police dogs. One man did his best to stay out of Vietnam, then spent years wondering what he’d missed. A woman who wrote a friend one week into his tour of duty got the letter back, unopened. He didn’t live to read it. A widow only recently learned her husband had served in Vietnam; she discovered that while going through his papers after his death. One fellow recalls running through his college dormitory, deliriously happy that he’d gotten a high draft number. He passed other students who sat sullenly on their beds, letters in hand. A broad-shouldered Native American, handing me a book to sign, describes with pride how his platoon buddies called him Chief. “Anybody else, I wouldn’t let them do that.” A high school dropout from Brooklyn carried his platoon’s radio in Vietnam. Its antennae made him a ready target. But he survived his year in-country, earned a Ph.D. and became a leading authority on English composition. A Chicago fellow got drafted after one year of college and was so traumatized by his war experiences that he couldn’t return to the classroom. His dream of being a history teacher evaporated. A Washington state man survived four tours as an Army aerial gunner. He kept re-enlisting because he thought his talent for killing was keeping Americans alive. He returned home unscathed, became a long-distance trucker, then nearly died after a driver pulled in front of him. He married his nurse, raised a family and bought an Illinois tavern. Though I sometimes overdose on the subject of war, I haven’t tired of hearing stories or meeting veterans. I admire their resilience. I look beyond their gray hair and see them standing bronzed, slender and bare-chested in the red soil of Vietnam. I imagine them sitting down in a tavern, like the one in Illinois, laughing with Grady as he mimics helicopter sounds and talks about his crazy, explosives-happy buddies—including the ones who, eyes wide with fear, came running to save his life, “just like in the movies.” Julie Titone’s writing and photography have appeared in Northwest regional, national and international publications. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed