By Julie Titone This powerful work by artist Grady Myers is not among those included in his memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." This Memorial Day seems a good time to share it. Perhaps the soldier he imagined when he created this survived his battlefield wounds, as Grady did. Perhaps he lived with the pain for decades, as Grady did before his death in 2011. Sadly, Grady never had a gallery exhibit of his work. But it's good to know that most of his war-related art is included in the collection of the National Veterans Art Museum.

2 Comments

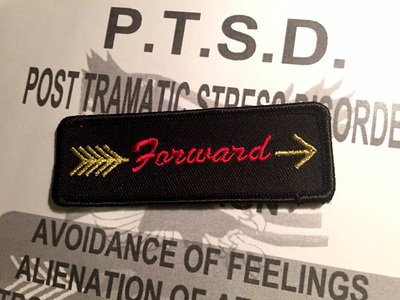

Paul Ridley with Julie Titone, co-author of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" Paul Ridley with Julie Titone, co-author of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" By Julie Titone Paul Ridley was an Army explosives specialist in the Vietnam War. On patrol, he frequently walked ahead of American troops to find and disarm booby traps. He blew up bridges. He dealt with bodies by the hundreds. Paul returned to Washington State in 1969 with a chest full of medals that included the Purple Heart for combat-related wounds. He ended his 12½-year Army career as many veterans of the era did: He didn’t talk about his military service. He got divorced. He drank. “I came back extremely isolated and stressed out,” he recalls. “I was a mess.” He pulled out of the tailspin in part by clearing minefields of isolation and bureaucracy so other traumatized veterans could move on with their lives. He's been doing the volunteer work for nearly 40 years, with the help of fellow vets and his wife, Karen. Paul made a living as a bricklayer and musician, which put him in touch with a lot of vets. On job sites and in bars, he saw turmoil and chaos in their ranks. In 1977 he moved from the Seattle area north to his roots in rural Skagit County. He played bass in Karen’s uncle’s band, “making good money and living with a lot of stressed-out vets.” Some were known as trip-wire vets. They’d move into the woods and set up wires around the perimeter of their homes or camps, attaching cans as noisemakers so no one would sneak up on them, just as they did in Vietnam. They took their stress out on their families, went jobless. Many had no idea what veterans’ benefits were available. Paul and friends started the North Cascades Vietnam Veterans Rap Group, an outlet for vets to talk about their experiences. That morphed into Operation FORWARD. “I gave them the motto ‘FORWARD’ so they would look to the future instead of dwelling on all the baggage we were carrying,” Paul says. “Our creed was to help anyone, any time, any place, any way we can. We gave them a patch so they knew they belonged to something.” Paul, who had climbed the Army ranks from private to warrant officer, put his organizational skills to good use. Likewise, he used his local connections to find people who needed help. He and Karen are from Native American and pioneer families, and know people from all walks of life. “I went to people I knew who owned gas stations, businesses, bars and such; in the fishing, the logging communities; the farmers; on the reservations and the Grange halls.” The first step in helping a vet might be getting him sober, fed, housed, or helping his family. The volunteer vets learned what social services were available. They dug into their pockets to help, and Paul sometimes landed grant money. Mostly, the volunteers learned how to navigate the maze of Veterans Administration paperwork to get disability pension checks or health benefits for vets, and they helped vets keep critical appointments. Sometimes, says Karen Ridley, it’s been necessary to get veterans to rein in their anger. “We tell them to be nice to the secretary and others on the front lines who can help your cause.” PTSD: A real problem One of the handwritten testimonials to FORWARD that Paul keeps on file is this note from George, a Navy vet who found himself on a Bellingham beach with no money and no self-esteem. “I didn’t have a plan of survival and didn’t care.” He was approached by a volunteer, a tall Green Beret vet, who asked him when he’d come home from Vietnam. And when he’d last eaten. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed