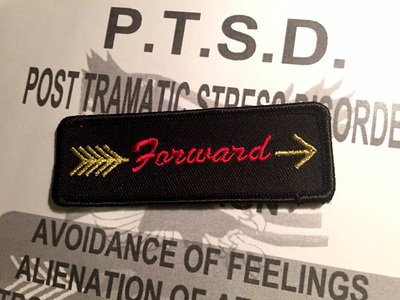

Paul Ridley with Julie Titone, co-author of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" Paul Ridley with Julie Titone, co-author of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" By Julie Titone Paul Ridley was an Army explosives specialist in the Vietnam War. On patrol, he frequently walked ahead of American troops to find and disarm booby traps. He blew up bridges. He dealt with bodies by the hundreds. Paul returned to Washington State in 1969 with a chest full of medals that included the Purple Heart for combat-related wounds. He ended his 12½-year Army career as many veterans of the era did: He didn’t talk about his military service. He got divorced. He drank. “I came back extremely isolated and stressed out,” he recalls. “I was a mess.” He pulled out of the tailspin in part by clearing minefields of isolation and bureaucracy so other traumatized veterans could move on with their lives. He's been doing the volunteer work for nearly 40 years, with the help of fellow vets and his wife, Karen. Paul made a living as a bricklayer and musician, which put him in touch with a lot of vets. On job sites and in bars, he saw turmoil and chaos in their ranks. In 1977 he moved from the Seattle area north to his roots in rural Skagit County. He played bass in Karen’s uncle’s band, “making good money and living with a lot of stressed-out vets.” Some were known as trip-wire vets. They’d move into the woods and set up wires around the perimeter of their homes or camps, attaching cans as noisemakers so no one would sneak up on them, just as they did in Vietnam. They took their stress out on their families, went jobless. Many had no idea what veterans’ benefits were available. Paul and friends started the North Cascades Vietnam Veterans Rap Group, an outlet for vets to talk about their experiences. That morphed into Operation FORWARD. “I gave them the motto ‘FORWARD’ so they would look to the future instead of dwelling on all the baggage we were carrying,” Paul says. “Our creed was to help anyone, any time, any place, any way we can. We gave them a patch so they knew they belonged to something.” Paul, who had climbed the Army ranks from private to warrant officer, put his organizational skills to good use. Likewise, he used his local connections to find people who needed help. He and Karen are from Native American and pioneer families, and know people from all walks of life. “I went to people I knew who owned gas stations, businesses, bars and such; in the fishing, the logging communities; the farmers; on the reservations and the Grange halls.” The first step in helping a vet might be getting him sober, fed, housed, or helping his family. The volunteer vets learned what social services were available. They dug into their pockets to help, and Paul sometimes landed grant money. Mostly, the volunteers learned how to navigate the maze of Veterans Administration paperwork to get disability pension checks or health benefits for vets, and they helped vets keep critical appointments. Sometimes, says Karen Ridley, it’s been necessary to get veterans to rein in their anger. “We tell them to be nice to the secretary and others on the front lines who can help your cause.” PTSD: A real problem One of the handwritten testimonials to FORWARD that Paul keeps on file is this note from George, a Navy vet who found himself on a Bellingham beach with no money and no self-esteem. “I didn’t have a plan of survival and didn’t care.” He was approached by a volunteer, a tall Green Beret vet, who asked him when he’d come home from Vietnam. And when he’d last eaten. The FORWARD folks put George in touch with two counselors, themselves veterans. He wrote: “I have probably been more trouble to these men than I’m worth, but I owe these men my life.”

If Paul seemed overzealous at times, well sometimes that's what it took to get people help. He faxed torrents of paperwork, got hot under the collar. His strong language got him temporarily banned from the tribal court of the Lummi Nation, where he would testify on behalf of tribal members who were in trouble. But that issue got resolved. The tribe has been a source of support for FORWARD. Though only one-eighth Native American himself, he lives among the Lummis on one of several Indian reservations he has called home. Paul is proud to be called White Buffalo, a name given to him 25 years ago by the Lummi warriors association. They gave him that name, he says, because they believe he can bring people of different backgrounds together. Karen is a former social worker who, when she met Paul, was working with rape victims and battered women. She’s well aware that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) isn’t confined to combat veterans. It used to be hard finding people who accepted that PTSD was a real problem, Karen says. One of the experts who put PTSD on the national radar is retired clinical psychologist and Marine veteran Tom Williams. He joined FORWARD’s cause in 1997 after Paul and Earle Terry, another FORWARD stalwart, approached him at the Bellingham Veterans Affairs office and pressed a business card into his hand, offering help if he needed it. For years, FORWARD took its show on the road for two weeks each spring. The volunteers would visit reservations throughout the Northwest, holding workshops and offering help filling out VA forms. Tom would go along, training local police and firefighters to recognize PTSD. Calls from help from around the country Many of FORWARD’s members have died. And, with more public services available to veterans, there is less need for its type of outreach. But Paul and Karen keep working from their home north of Bellingham, an old schoolhouse with a brick façade that is Paul’s handiwork. His cell phone rings with calls for help from around the country. “We have a huge turnover of people who come here because it’s as far as they could go on I-5,” Paul says of wandering veterans who would follow the interstate highway that ends at the Canadian border. “When we win their (VA) claims, they go back to where they came from.” For example, FORWARD helped one Iraq War veteran qualify for a $3,000 monthly disability check. The fellow returned to the South, where “his dad went to the tavern and told everyone,” Paul says. “Now I have nine claims from Lawrence, Ky.” Paul leaves e-mailing to Karen. He doesn't mess with computers himself. “I’m not a clerk, but I know how to talk to veterans,” he adds. “I mail them the forms, all filled out, with pre-addressed, stamped envelopes. I put stickers on the forms with arrows showing them where to sign. I hook them up with counselors, which gives them information they need in support of the claim.” Karen credits Paul’s natural-born leadership skills with his success at helping others. “He doesn’t know the meaning of the word ‘can’t.’” Paul is 75 and his hearing isn’t what it used to be. But he has no plans to stop helping veterans. It’s like playing his guitar. He’ll do it as long as he can. “Why would I quit? I don’t drink, don’t gamble, smoke or do drugs. I’m not religious,” he says. “I have something to do that matters.”

13 Comments

Megan

5/7/2016 03:50:39 pm

Paul & Karen helped two of my very best friends--a vet and his wife--get through some very bad times and find the help and resources they needed, I'm so grateful for all they did and equally glad they're getting some recognition for all they've done.

Reply

Julie Titone

5/10/2016 12:26:36 pm

Aren't they great? Thanks for sharing.

Reply

Jesse Brand

12/3/2016 12:22:34 pm

I've known Paul Ridley since the day I was born. He grew up with my dad, and went to Vietnam with my uncle. He is as close to being my family as you can possibly be, without sharing blood. His kids and I grew up together. He was my neighbor. He used to park his horse in my back yard and walk back to the old Bob's/Shanghai/Malibu to listen to my dad's band play. He had (maybe he still does) a beautiful Telecaster which he used to let me play, when I was a mixed up young teenager, and would walk the several miles out to his place on the Res, and he always had a couch for me to sleep on. He is an honorable man. He is one of my heroes. He is my friend... and if he's ever in Nashville, he's got a place on any stage I'm playing on. - Jesse Brand, Academy Award Winning Songwriter

Reply

Pete Ridley

10/19/2022 11:49:50 am

Hi Jesse, I heard about you at Dad's funeral. Karen told me the story with parking the horse and your success as a musician in Nashville.

Reply

Cheryl Ogden "Charlie"

5/29/2017 04:41:23 pm

I have known Paul for many years. He always gave of himself and never asked for anything in return. Every time I return home to Belllingham, Washinton I make it a point o go see him and Karen

Reply

Arthur Lorraine Chapel

1/14/2019 01:12:08 am

Paul Ridley-Hello my devoted brother! I love you Paul. You and the likes of Mke Withey of Seattle have made my life tolerable. I pray daily that the Donald will find a way in God's Great name to become a great punisher of all known now as THE SWAMPSTERS.... I think of you often. As a real MAN . GOD BE WITH YOU ALWAYS MY FRIEND. REAL: ART CHAPEL- 237 W. STATE ST. #1- 84737. THANKS PAUL.

Reply

Art L. Chapel

1/14/2019 01:47:22 am

.....just one more thing Paul? My uncle ( Boise , I'd. Now deceased Earl Chapel, was a 1st airborne sniper... He was messed up his whole life from PTSD... it's very sad...how do I get his records , medals etc? I cannot find a thing & I'm always broke & living in a 1 horse town...hurricane Utah....and then there's the problems I'm fighting daily concerning my lowlife, well known , daily reported by name to every concievableb federal agency, since 09 cyber thief fraudsters.....but I've tried for years to get my uncle's info. Thanks again - anything I can do for you here ? Consider it done. Thanks again. Art-84737

Reply

Art L. Chapel

1/14/2019 07:52:19 am

I read that you are not religious Paul, but at our age ....I want you to Google " planet x 2019" and find new meaning in your life...I want to see you on the other side!!! Trust in

Reply

Max stephens

9/2/2022 08:01:20 am

Paul and Karen literally saved my life

Reply

Dale Boe

9/5/2022 02:02:13 pm

The list of people Paul has helped is long. He gave every vet hope. In the 80s he came into a tavern I owned called Snuffys Tavern and asked if they could have a meeting once a week and the newly formed group came to life. Every Friday they would come in and gather around the oak table and the group Forward. Northwest Cascade Mountain Vietnam Veterans Rap Group, Brant Island Foreign Legion was born.

Reply

Rosemary Handerson

4/29/2024 11:36:51 am

My brother Paul also made a small stone house for my fairy garden. I cherish it. He is very much loved as is Karen.

Reply

Dale Boe

5/10/2024 11:50:31 pm

I owned a bar in Bellingham called Snuffys Tavern and Paul would come in then on day he asked if he could bring some vets in each week and have a meeting at my oak round table and the group called Forward was born. Paul gave me some business cards with my name and motto for the group. I would find vets needing help and introduce them to Paul and get them signed up for benefits. I was a vet and this gave me something to feel like I was worth something. Paul passed away a few months ago and it is a loss to us all. So save me a seat at the round table and we can get back to work doing what you do best helping fellow veterans. You are a good man Paul I miss our times.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed