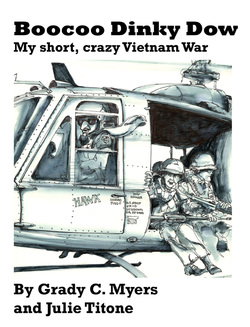

Doyle McClure of Moscow, Idaho, sent the following review. Many thanks, Doyle. - jt This small, intense book can be read on several levels. Most directly it is Grady Myers’ unsentimental “I-am-a camera” account of his approximately 18 months in the US Army as a combat infantryman during the Vietnam War. This culminated in a chaotic firefight in which Grady was seriously wounded He received a Purple Heart, then spent many months in Army hospitals undergoing surgery and rehabilitation, ultimately being left with life-long disabilities. The memoir might also be regarded as the coming-of-age story of a 19-year-old genial giant who, after a brief, unrewarding sojourn at Boise State College, volunteered for the draft and was almost immediately sucked into the maw of the U.S. Army. The book reveals his determination to “make the grade” when subjected to the Dr. Strangelove-like world of Army training and battle. Although nearly blind without eyeglasses, Grady became an expert marksman. He was given the nickname “Hoss” and the assignment of manning a 23-pound, M-60 machine gun. In addition to being an extra burden on the hot, steep terrain of Vietnam, the M-60 made him a special target for enemy fire. The book's approach is “this is how it was." It is largely unencumbered by opinion or any indication of bitterness. On another plane, however, the book might well be regarded as an anti-war expose, carried by a chaotic succession of “crazy” events. As suggested by the title, which is GI shorthand for the Vietnamese beaucoup dien cai, generally translated as “very crazy in the head,” the book recounts a cascade of frequently bizarre actions of troops and officers. Although in many cases such actions endangered (and wounded or killed) both troops and innocent Vietnamese civilians, in the climactic battle scene a medic and other men in his brigade heroically rescued Grady at great risk to themselves. Only in the final paragraphs do we see Grady’s post-war perspective on Vietnam. As explained in the preface and epilogue by his co-author (and prior wife) Julie Titone, and as shown by the many illustrations, Grady Myers became a talented commercial artist, beloved by friends and family. The dramatic human aspects of the story rest both on his reporter’s eye for detail and on the ability to impart vivid imagery. In no small part, the power of the story also rests on the abilities of writer, Julie Titone, to structure and translate the oral stories to the written page, retaining the drama and bringing to life the many individuals who populate this compelling narrative. Doyle McClure_

3 Comments

7/31/2013 09:38:51 pm

I read the book My short, crazy Vietnam War recently. I got this book at a reduced price because I had an offer when I bought an Amazon Kindle. It was by chance I read it, and I should say, your book is so good.

Reply

Julie Titone

8/1/2013 03:03:23 am

Thank you so much! Have you thought about writing an Amazon review? I love to know what people think of the book, and am not worried about the number of stars :-)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed