By Julie Titone No disrespect to the folks who were moved by it, but I had to click off the TV about 10 minutes into Sunday's Memorial Day concert from the National Mall. The overly groomed singers belting out patriotic songs clashed mightily with the complex, unscripted emotions I have confronted in conversations about battlefield sacrifice and its aftermath. I've had many such talks during the last few years of sharing the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." What did move me this Memorial Day were commemorations that arrived in my email box in the form of unpublished writing by two Army veterans, Michael Simpson and Carroll McInroe. I was honored to read their work. It made me think not only of those who died in the service, but also what died inside many of those who made it home. 'I had to lay down my soul' Michael Simpson, who served in Vietnam in 1967, sent chapters from a memoir so powerful I had to stop reading from time to time. In one of them he described how a Vietnamese boy, who sold Coca-Cola to the troops, stepped on an anti-personnel mine that had been planted under a tree. The blast vaporized him from the waist down and flung his upper body into a road, right where a convoy was headed. The platoon leader yelled for someone to move the corpse. When none of the other stunned soldiers responded, Michael stepped forward to do what should have been a gut-wrenching task. He writes: "This had been a kid I had known and liked, a bright, curious boy, and as I felt his hair between my fingers and dragged his dead body through the dust, I was dead inside. This is what bothers me. I felt nothing. Even to this day, as I write this, I find it troubling that when I cry at the memory, I am not grieving for this boy and the loss of his life; I am grieving for the loss of humanity within me. When this child died, and I performed this small service for my country, an insignificant thing really, drag a light object a few feet out of the road, I had to lay down my soul to pick up his head in my hand." Post-traumatic stress disorder? For decades, that wasn't something Michael thought had anything to do with him. Not even when he pushed away memories of holding a fellow soldier who died in his arms, intestines spilling out on them both, a medic nowhere in sight. Not even when his life was falling repeatedly apart. Michael is a Veterans Justice Outreach volunteer in Lewiston, Idaho. He also serves as mentor coordinator for Veterans Treatment Court. He plans to publish his book, in hopes it will help parents understand what their children could face if they go into the military. Its working title is "The Road from Happy Valley: A Pacifist's Viet Nam Experience." 'Backhoes biting holes in the earth, day after day' Texas-born Carroll McInroe served during the Vietnam era and went on to a career in the Veterans Administration where, he said, "we knew PTSD before PTSD had a name." He lives in Spokane, Washington. He wrote the following essay, titled "Waco V.A.," in the 1970s. As I entered the V.A. hospital ward, I saw my old classmates, Catfish, Gary, Ross, Richard and Avis. I saw our former Commander-in-Chief, President Richard Nixon. We soldiers did not like him much, you know. I saw Walter Cronkite telling us why and later why not. I saw long lines of teenagers being inoculated and indoctrinated. I saw the distant stares of boys fresh from battle, as we ferried them from the airport to the barracks – a hot meal, a warm bed at last. I saw the anguish, the guilt, the confusion on the faces of hundreds of other boys, as they formed yet another line to give blood, month after solemn month, for their young comrades-in-arms over 10,000 miles away. I saw backhoes biting holes in the earth, day after day, for American teenagers who no longer bled. I saw other teenagers, privileged confident ones, taunting Gold Star mothers at the gravesides of their sons. “Baby killer” was the common phrase. “Killed in Action” read the letter. “From a grateful nation,” said the flag. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, names on a wall. I saw hallways and drill fields, filled with young enlisted men, enraged over the killings at Kent State. It was 1970. I saw the same halls and fields filled with shouting senior NCO’s, demanding obedience, screaming “the college kids got what they deserved,” threatening courts-martial for any young G.I. rebel who disagreed. I saw an old friend rolling a joint with shiny metal hooks where his hands had once been. He had continued to man his M-60 as his arms were literally shot to pieces by NVA rifle fire. “I had to keep shooting or we were done. Those little people, they never quit.” The girls sat mesmerized, stoned, silent, wondering what had happened to this good young man. His girlfriend had walked out of his life because he was a war-monger. The local police were scouring the streets for him because he was “involved with drugs”; former friends and family shunned him. “Dirty long hair, bunch a’ bums.” He took a deep toke and told me, “I have nowhere to go – prison I suppose.” We spent the evening, getting high, talking, listening to Jethro Tull. I don’t know where this friend is anymore. I don’t know much of anything anymore. I know where Cat, Gary, Ross, Richard and Avis are. Their families leave a small flag at their grave sites once a year. Now listen carefully, you rare few. My classmates survived the Vietnam war. It was the homecoming that killed them.

2 Comments

11/13/2022 10:43:05 am

Official ready write base. Rich section right he.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

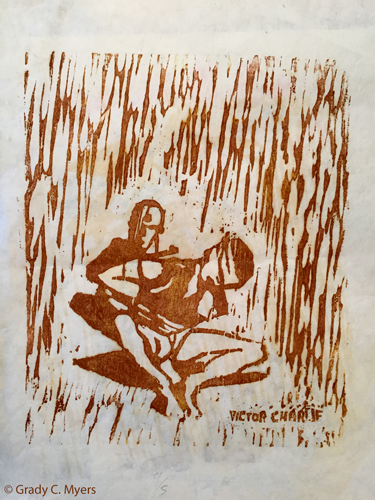

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed