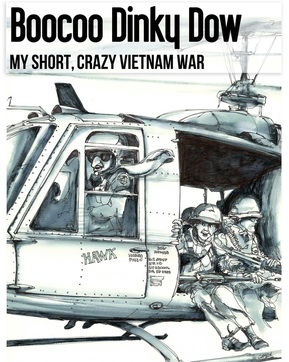

Click image to read library poster Click image to read library poster By Julie Titone It will be an honor to read from "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" on April 30, the 40th anniversary of the day the war ended. Skyway Library will host the 7 p.m. program. By the time Saigon fell to North Vietnamese troops, Army veteran Grady Myers had been out of the combat zone for six years. His Purple Heart was packed away; his battle wounds were as healed as they were going to be. He had finished his art studies in Seattle, was about to launch a career, and had begun telling friends the stories that decades later became his memoir. When I first heard his animated stories -- his helicopter sounds were second to none -- I thought of the TV series "M*A*S*H," with its dark and deeply humane subject matter punctuated by humor. Of course, that 1970s hit was really about Vietnam, but set in Korea to make it more politically palatable. The title "Boocoo Dinky Dow" comes from the soldiers' pronunciation of a Vietnamese phrase meaning very crazy. It wasn't published until after Grady died in 2011. Back in the late '70s, when Grady and I became a couple and worked together on a first draft of the memoir, publishers weren't interested. They said no one wanted to read about Vietnam. Now there is an explosion of stories about the unpopular war. Men and women who served in Vietnam, some of whom haven't spoken for decades of their experiences, are opening up. As I describe in the essay Author connects with Vietnam veterans, I'm delighted to be among those calling attention to the sacrifices of a generation of vets, both those who served in combat and the many more troops who supported them. I look forward to meeting more veterans in Skyway this Thursday evening. And I hope that, after sharing some of Grady's stories, I'll get to hear some of theirs in return.

1 Comment

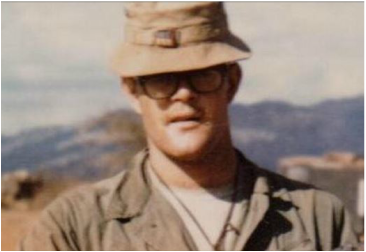

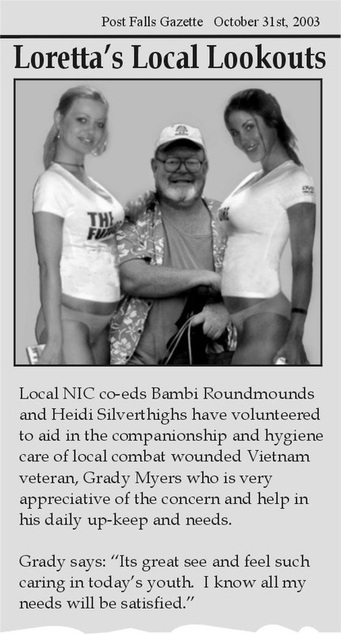

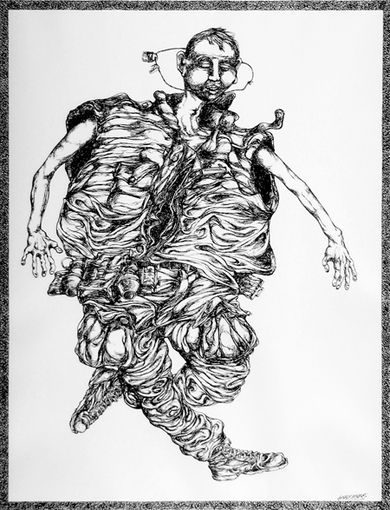

Click to read the library poster Click to read the library poster By Julie Titone When officials around the country designated Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day -- here in Washington state, lawmakers chose March 30 -- they did more than honor combat veterans. They gave us all a chance to reflect upon a time of upheaval, change, controversy. We who lived through the era know the war was formative for both our country and ourselves. Those who weren't born until after 1975, when the United States dramatically pulled its last troops out of Saigon, should understand the history behind the phrase "another Vietnam." This March 30 will be especially meaningful for me. I've been invited to give a reading that day from "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" at Bellevue Library. The Monday event will start at 3 p.m. I am co-author and instigator of the book. But it is entirely the story of Grady Myers, a wonderful artist and wry observer of human nature. Grady and I were married during the 1980s; he died in 2011. In Grady's absence, I often have male readers join me at presentations. In Bellevue, I'll have two guests. Bellevue veteran Bob Shay was a Navy photographer who served in the Pacific during the war and tried his best to get sent into combat (I'll let him tell that story). Charley Blaine is a Woodinville writer and editor. A former colleague of mine and Grady's, Charley is a fine storyteller, too. After we read some book excerpts, I'll show images of Grady's war-related art. Coming up: On April 30, the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, I'll present "Boocoo Dinky Dow" at 7 p.m. at Skyway Library.  Tom Williams holds a picture of himself grieving Tom Williams holds a picture of himself grieving By Julie Titone A young Marine officer in Vietnam sits alone, holding his bowed head in his hands. He has just lost 13 men in combat. A photo capturing that moment became part of the Veterans Administration case file on Tom Williams, helping confirm his diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Tom not only knows what PTSD feels like, he knows how to help others who suffer from it. After the war he became a clinical psychologist who edited two seminal books on the subject published by the Disabled American Veterans: "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders off the Vietnam Veteran" (1980) and "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders: A handbook for clinicians" (1989). He would own more copies of those books except that he was asked, after 9-11, to send them back to New York and to the Pentagon, so they could be used to help treat people traumatized by the terrorist attacks. Tom is the latest of the kind, resilient veterans who have agreed to help me out at public readings of “Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War,” which Grady Myers and I wrote. They stand in for Grady, who survived his battlefield wounds but died in 2011. Tom will be my guest reader at Village Books in Bellingham, on March 28 at 4 p.m. These days, Tom is retiree with a dynamite grin who meets other vets regularly for breakfast, brotherhood and shooting the breeze. He invited me to join them recently at the Curious Chef, an aptly named place for me to ask about their military experiences and them to turn the tables with questions for me ("So, what did you think of the war back then?" and "What caused Grady's death?"). They let me snap their picture, shown below. Their camaraderie brought to mind what Tom told me about veterans who recover from the trauma of war. He cited a nationwide survey of 200,000 Vietnam veterans. “It was a beautiful, expensive study," he said. "They came up with a couple of things: The guys who are doing well have a stable relationship with a woman, and they have contact with fellow survivors." Tom lives in a riverside home set apart from the world among the firs of Whatcom County, Washington. When I visited him there, he patiently answered my questions about his life and work even though the sun was shining and he was eager get out on his red Ural motorcycle, which has a sidecar for his lady. A sunny day in the North Cascade Mountains is not a thing to be wasted indoors. We talked about how the movie "The Deer Hunter" made him realize the war’s impact on his psyche; how he and his colleagues designed a national model for helping distressed veterans; how families like his and mine are affected by the ripple effects of stress. We also talked about the persistent “crazy vet” stigma; how the Veterans Administration lost its way; and how humor, like that which punctuates “Boocoo Dinky Dow,” is so important to mental health. I'll elaborate on Tom's experiences and ideas in an upcoming blog post. I’ll also reflect on my last few years of sharing Grady’s stories. It’s been an enriching journey during which I’ve learned a lot about history, and a little about myself.  By Julie Titone This is my candidate for the most unlikely and smile-inducing photo from the Vietnam War, a cross between Beach Blanket Bingo and China Beach. My excuse for posting it is to help locate that second soldier from the right, Tim Crowder. Tim's high school buddy Ray Heltsley is looking for him. Ray joined me at a recent reading from "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." He brought along a boonie hat that was worn through two tours in Vietnam -- first by Tim, the Marine; then by Ray, the Army Ranger. When Tim passed the hat along, he said he'd won it in a surfing contest at Da Nang. Ray wasn't quite sure whether to believe that, even though the word SURF is stitched on the boonie. But last week Ray searched the Web for Tim's whereabouts and came across the Marine Corps photo from the National Archives. Its caption: Surfing--Captain Rodney Bothelo, 1st Shore Party Battalion, and Miss Elli Vade Bon Cowur, Associate Director USO, judges for the OSO sponsored surfing contest held September 25, 1966, are shown with Private First Class Robert D. Binkley, FLSG-B, who took first place in the event; Corporal Tim A. Crowder, Communications Company, Headquarters Battalion, second place winner, and Lance Corporal Steven C. Richardson, 1st medical Battalion, third place winner. Tim and Ray were classmates at Seattle's Bishop O'Dea High School. "Tim graduated from O'Dea in 1963," says Ray. "I left O'Dea at the end of my junior year, and graduated in 1963 from Chief Sealth High School. I recall that he tried to contact me some time around 1990-ish, but I missed that info and found out about it from my Dad later. I never managed to hook up with him, and he probably thought I didn't care at the time. I'm hoping that he would be receptive to a contact now." When Tim returned from Vietnam, he gave Ray the hat and then "disappeared into California." If you know where that surfer dude is hanging 10 or just hanging out these days, drop us a note. We'd also like to know where those other folks in the picture ended up, and learn the scoop on that surfing contest. Was it a one-time thing? Ray read that it may actually have been at Chu Lai southeast of Da Nang, though an undated video clip of soldiers on R&R prominently shows a "no surfing" sign there.  Grady Myers in 1969 Grady Myers in 1969 If you want to honor a Vietnam vet, you could pick no better hat to doff than a boonie, aka a bush hat. The brimmed cotton topper was a point of pride for infantrymen like Grady Myers. As Grady recalls in "Boocoo Dinky Dow,: My short, crazy Vietnam War," he found his on a dusty parade field in Dak To. "Bleached by the sun from green to tan, it had a narrower brim than the newer bush hats. It would definitely give its wearer that old-timer look, and I was pleased to find that it fit my big head. "The baseball-style cap I’d been wearing was scorned by many of the infantrymen, who associated it with training. But I had creased its bill and roughed it up to make it look reasonably veteran-ish—enough so that Johnson, who had lost his hat during guard duty the night before, was delighted when I passed it along to him."  At a recent "Boocoo Dinky Dow" book reading, veteran Ray Heltsley showed with pride a camouflage pattern boonie that had seen two tours in Vietnam -- first on the head of a friend, then on his own. The word "SURF" is stitched on it.. When I asked Ray later for details, he replied: "The boonie hat was given to me by a former O'Dea High School classmate, Tim Crowder, who went to Vietnam as a Marine in 1966. He told me that he won it for taking 2nd Place in the Da Nang Surfing Championships. The fluorescent pink material inside the hat is a piece of an aircraft signalling panel. When the hat is turned with the panel pointed upward, you can pop it open and closed and it becomes a visible signal so that an aircraft can spot your location." The back of the hat is trimmed with luminous tape called following tabs, Ray added. "They glow in the dark, so that the person behind you can follow you silently without losing track of you and breaking silence by calling for you. It's all pretty much Ranger protocol, and most of the people in the line units didn't do this kind of stuff." Vets like Ray are delighted by the detailed descriptions Grady put into his memoir. The hats, the knives, the ham-and-lima-bean meals remind them of their time of intensive living in Vietnam -- which, along with its profound miseries, had traditions and habits they will never forget.  Ray Heltsley in March of 1969 at Fire Base Concord in Cong Thanh. He was leaving for a night ambush with a platoon of ARVN (South Vietnamese troops). This was the same month that Grady Myers was seriously wounded when his own platoon was ambushed by the North Vietnamese. Ray Heltsley in March of 1969 at Fire Base Concord in Cong Thanh. He was leaving for a night ambush with a platoon of ARVN (South Vietnamese troops). This was the same month that Grady Myers was seriously wounded when his own platoon was ambushed by the North Vietnamese. Ray Heltsley is a retiree on Whidbey Island in cool Northwestern Washington. In 1969, he was in tropical Southeast Asia, a U.S. Army adviser working side-by-side with the South Vietnamese. Ray, who will join me at a Nov. 6 reading of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short crazy Vietnam War," got a perspective on the Vietnam War that most American soldiers were denied. He got to know individual Vietnamese, developing friendships and professional respect for them. Ray was a lieutenant; Grady Myers was a private. Ray went to 'Nam as a college graduate; Grady was a dropout whose professional training was still in the future. But when Ray read "Boocoo Dinky Dow," Grady's memoir, he related strongly to many of Grady's experiences, starting with the moment he stepped off a plane in Vietnam. In "Boocoo Dinky Dow," Grady recalled: "It was the second evening of our long day when we arrived at Tan Son Nhut airfield outside Saigon. When the jet door swung open, it let in a blast of hot air. When I stepped outside, I felt as if a damp blanket had been thrown over me." Ray describes the experience this way: "When I got off the plane, I thought 'I have to get away from this plane exhaust.' But when I went in the terminal, it felt just the same." Ray arrived in-country with some understanding of the Vietnamese language, politics and culture, thanks to Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Assigned to work with the South Vietnamese troops -- many of whose officers had fled North Vietnam -- he got a strong figurative and literal taste of the culture. While other GIs were told not to eat food prepared by locals for fear it might be poisoned, Ray learned what was safe and scarfed it down. "I ate monkey and dog," he recalls. "I kind of drew the line at fish soup that has eyeballs." Ray also experienced combat. Felt fear. Identified lots of bodies. He, like Grady, had to decide when to fire his weapon. He recalled choosing not to kill an enemy who was caught literally with his pants down because it wasn't the way HE would want to die. Ray went on to a law enforcement career. But he studied journalism in college and that training is evident in his own well-written 85-page Vietnam memoir. In it, he summarizes his experiences in a way that could've come from straight from Grady and the other veterans who've been kind enough to join me at "Boocoo Dinky Dow" readings in Grady's absence. He writes: "I have lost the sharp memory of the order in which my adventures unfolded, but they lie jumbled in the corridors of my mind, stark and real memories of an experience that I wouldn’t have missed for the world and would never want to repeat."  Birthday cards, Christmas cards, baby shower announcements ... if you could get Grady Myers to illustrate one of those, you had a treasure in your hands. The guy had a real sense of whimsy and was generous when friends came asking for him to illustrate this or that poster, card or souvenir for them. One especially popular item was the annual T-shirt he designed for the Bare Buns Fun Run. Grady was a newspaper artist for much of his career. So he loved the fake headline/news story approach. Using a picture snapped by a friend, he created this fun story shortly after his 54th birthday. this was during the years he worked for the U.S. Forest Service. The "NIC" mentioned in the caption is North Idaho College. Grady would have been 65 years old today. For those of us missing his over-sized spirit and talent, it is some consolation that we had him around until he was 61. Because he came awfully close to dying as a young soldier in Vietnam. That ambush chapter is the most intense part of his memoir, "Boocoo Dinky Dow." The book has some funny moments, too. If you've read his description of the comely United Airlines attendants who were on his flight to Vietnam, you won't be surprised by the "lovelies" he chose for this picture.  Jess Walter and Sherman Alexie Jess Walter and Sherman Alexie I was in my kitchen the first time I ever responded out loud to a podcast. “Exactly!” I said after author Sherman Alexie veered a conversation about football to the subject of military veterans. Sherman and his friend Jess Walter recently started the podcast “A Tiny Sense of Accomplishment.” The two men belong to the truly exclusive club of New York Times best-selling writers from Eastern Washington. I enjoy their audio mashups of thoughtful conversation and banter despite—or maybe because of—their occasional bursts of preteen humor. Halfway through that third episode, they interviewed Steve Almond, author of Against Football: A Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto. I began to feel unsettled. Though I'm not a football fan, I was relating to the conflicted tone of Almond’s voice as he described the many shadows cast by America's obsession with a dangerous sport. I stopped loading the dishwasher and listened intently. Then Sherman, whose Spokane Indian Reservation upbringing inspires much of his writing, commented almost without transition that Native Americans hold the military in high regard. That veterans are honored at powwows whether they served in combat or never saw a lick of action. That the warrior mystique is pretty ironic, considering “nobody has lost as completely, as totally and as easily as Native Americans.” Sherman had made the connection to a subject that’s even more complex than violent sport, one I’ve come to know a lot about. For the last three years I’ve been meeting veterans, delving into American history, and exploring military culture – all while sharing "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War,” the Grady Myers memoir that I co-authored. Along the way, I’ve been exposed to heaps upon mountains of conflicted emotions. I meet many men who take great pride in having “done their duty” in a war that hurt them physically, mentally or both. It was a war they didn’t understand then and usually don’t approve in retrospect. It was a war so synonymous with moral and policy failure that the phrase “Another Vietnam” yields 143,000 Google results. I know combat vets who feel guilty for surviving and even non-veterans who feel guilty for having stayed out. I know veterans who speak enthusiastically of visiting ‘Nam as tourists and others who recoil at the idea. I’m grateful to the former war protesters I meet, glad they spoke out to end the carnage. I also understand the pain of veterans who felt disrespected by the protesters. As I explained in an essay about the “Boocoo Dinky Dow” journey, I’ve developed a deep connection with vets. I have military family. No way would I write a book called “Against Veterans” or “Against the Military.” Could I write “Against War”? Definitely. Though it would be a complicated book. Because in addition to horror and waste, war yields friendship, pride, and the occasional vanquishment of evil. War is a stage for both despicable crimes and crystalline acts of conscience. As Grady’s book shows, war can inspire art and even comedy. Jess carried the podcast ably to the finish line when he noted that stories of victory and defeat permeate our lives. Shoulder pads and flak jackets. Astroturf and rice paddies. Sure, they’re different. Except when they’re not. My thanks to the “Tiny Sense of Accomplishment” guys for stirring up these thoughts. It’s what the best writers do.  Ed Bremer at the KSER studio Ed Bremer at the KSER studio I'm always fascinated to learn which parts of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" strike a chord with readers. For Ed Bremer, it was the story of the soldier who set out to kill his dog. Ed is news director for KSER-FM. When he interviewed me about the book I co-authored with Grady Myers, he asked me to read Grady's anecdote about Stiletto and his ailing puppy. The grunt in question was a gung-ho, let's-kill-Charlie type. He had an affection for knives -- which is why Grady dubbed him Stiletto. It wasn't a knife, though, but a .45-caliber pistol that Stiletto borrowed from Grady the evening he decided his dog had rabies and had to be dispatched. Things did not go as planned. Things went badly. Ed saw that episode as a reflection of trauma and conflicted emotions of many American soldiers in the Southeast Asian conflict. You can listen to the KSER interview here. The Stiletto story comes shortly after the 34:20 mark, where Ed is asking me if I had a moral or lesson in mind when I was assembling Grady's tales for publication. Ed asked lots of questions. Among them: Did Grady suffer from PTSD? Did I leave any of his war stories out of "Boocoo Dinky Dow"? How did the book come to be written? How did Grady's children react to it? One of Ed's memorable observations was that Grady struck him as a man of integrity. Which I agreed was definitely the case. Another memorable moment for me came right before the interview started. That's when I reminded Ed that as a writer and former journalist I would, truth be told, rather be the one asking the questions. "So would I," he replied with a grin. Then he put on his headphones and switched on the microphone.  "Still Life with CIB" by Grady C. Myers "Still Life with CIB" by Grady C. Myers The Grady Myers drawing "Still Life with CIB" is on display in Surrealism and War, which opens this Memorial Day at the National Veterans Art Museum. The work is among others from the NVAM's permanent collection that are included in the six-month exhibit and series of special events. War is almost by definition a surreal enterprise. That's certainly the impression I got when listening to Grady tell the stories that we captured in his memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." It's interesting that Grady chose the Combat Infantry Badge as the subject of this, the most abstract of his war-related works. Among his military decorations, he was most proud of the CIB. It meant he hadn't just served in the Army. He'd seen battle -- and, as this piece suggests, paid a price for that experience. This disheveled soldier does not fit his clothes and seems disjointed, harried. He has seen a lot. Are his eyes closed against memories of violence and fear? Surrealism, write the exhibit curators, is "an attempt to revolt against the inherent contradictions of a society ruled by rational thought while dominated by war and oppression. Surrealism seeks expression of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and free of aesthetic and moral preoccupation. It is this same absence of control exercised by reason that many combat veterans seek to explore and express after their experiences in war." "Still Life with CIB" is one of four pieces that Grady created in the 1990s for a traveling exhibit of work by Vietnam veterans. That project evolved into the Chicago museum, which is the repository of Grady's original Vietnam-related artwork. That art is reproduced in "Boocoo Dinky Dow." But the small-format book doesn't do justice to the original poster-sized works. It's wonderful to know they are occasionally brought out for public viewing. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed