"Still Life with C.I.B." "Still Life with C.I.B." By Julie Titone Six years of sharing Grady Myers's Vietnam War story has changed my reaction to Veterans Day. Maybe "intensified" would be a better verb. I've always felt gratitude on this holiday for folks who devoted part of their life to military service -- my dad, brother, son and friends among them. But ours was not a "military family," and my patriotism has not been of the flag-on-the-porch kind. It has been something I felt in my bones, especially when putting the First Amendment to practice as a journalist. But co-authoring Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War, publishing it after Grady's death, and doing my best to get it in readers' hands has affected me. I have met many more combat veterans. I've been moved and enlightened by the stories they shared with me in return. I've met their family members, and talked with folks who have deep and often conflicted feelings about both the Vietnam War and our military in general. In bookstores, museums and living rooms, people have come up to chat and opened their hearts. Here are two questions on my mind this Veterans Day. I'd appreciate your thoughts on them. As one Marine Khe Sanh survivor told me, "No one hates war more than a soldier." So shouldn't we have a Peacemakers Day to honor those whose work on making or keeping peace wasn't (or perhaps was) in uniform? Despite its humor and easy-to-read storytelling, "Boocoo Dinky Dow" is ultimately the story of a young, peaceful man forced to kill for a cause he didn't understand. Beyond telling stories like this, how do we do a better job teaching younger generations about the cost of war?

2 Comments

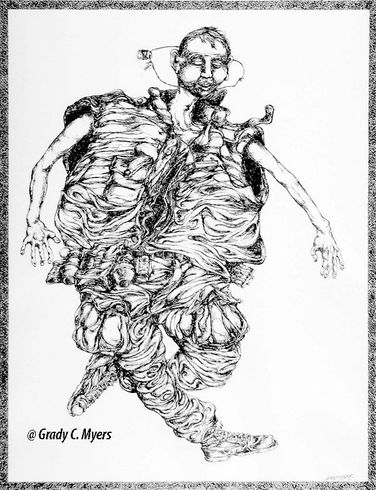

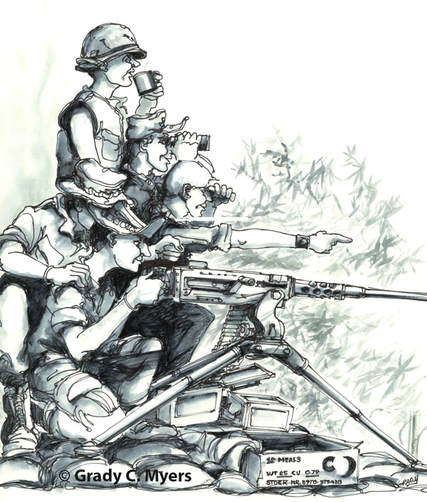

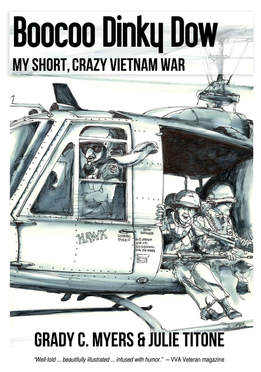

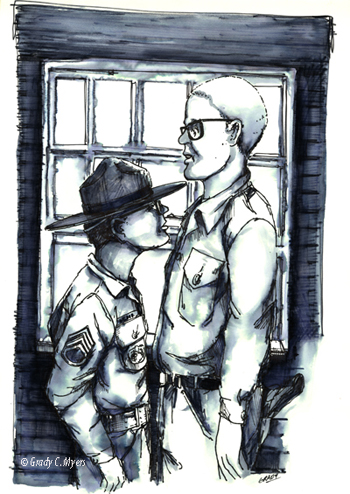

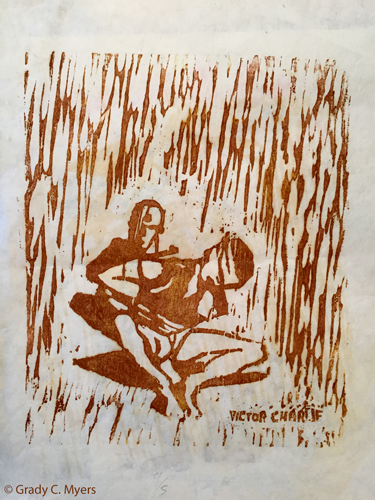

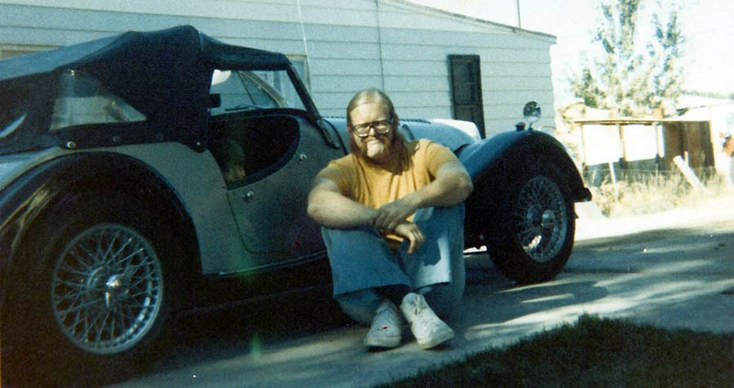

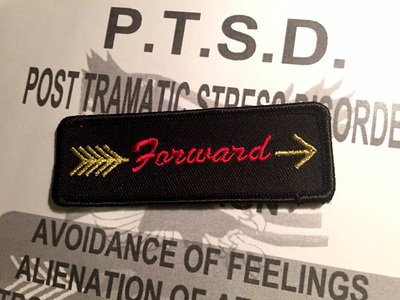

By Julie Titone Vietnam War vets are especially fond of this Grady Myers drawing from his memoir Boocoo Dinky Dow. It captures a sense of relaxed camaraderie -- the kind of moment a veteran can recall without pain. In the drawing, Grady is likely the fellow in the boonie hat, face hidden and hand on the shooter's shoulder. This excerpt from the book follows Grady's fateful acceptance of being assigned the role of M-60 machine gunner: After issuing the standard alert that the upcoming fire was friendly, they ensconced me on a bunker and directed me toward what served as the base firing range. I took aim at a tenacious limb that jutted from a gnarled, bullet-ridden tree 100 yards away. It had been the target of countless free-fire sessions. I proceeded to shoot it in half. My audience reacted with back-slapping glee. “Out-fuckin’-standing!” “Way ta go, Hoss!” “Hey, you’re pretty good.” I was pretty good with weapons, which was a source of pride to them all, especially (squad leader) Stotka. They liked to watch me in action during the daily mad minute. That was a free-fire period that served as a means of testing weapons and reminding the enemy of the American presence. The CO alerted the squad leaders of the exact time to start shooting, and they in turn passed the word to the troops. Every soldier dropped what he was doing, gathered his weapons and walked to the perimeter. Mad minute could be called at any time, but seemed to come most often at dusk. I suspected that the officers liked to watch the tracers shoot through the settling darkness. From my position, I could feel the setting sun on my back and watch the hill’s shadow fall on the orange-tinged mountains to the east. The animals below, clued to the coming barrage by the hubbub at the perimeter, chattered, squawked and—to the chagrin of us target-seeking marksmen—disappeared into the jungle.  Before there was email spam, there was pork, with ham, salt, water, modified potato starch, sugar, and sodium nitrite -- AKA, SPAM. In 1970-72 it provided sustenance to a trio of hungry Seattle art students. One of them was Joe Tschida -- who, upon seeing a SPAM commercial during the Super Bowl, was inspired to look up a couple of his old buddies on the Internet. One of them was Grady Myers. "I went to art school with Grady in the early 70s, when we'd make fried SPAM sandwiches every Monday night together," Joe said in an email, explaining what led him to this website about Grady's war memoir. "So sorry to hear of his passing. Just ordered Boocoo Dinky Dow on Amazon." This definitely tops the list of stories I've heard about how people found the book that Grady and I co-wrote. Joe knew Grady about eight years before I did, and heard Grady's war stories when they were truly fresh. Immediately after Grady recovered from the wounds he suffered in Vietnam, he used his veteran's benefits to enroll in the Burnley School of Professional Art (now the Art Institute of Seattle). "Mostly I remember a big, jolly, sarcastic and talented friend and not really bitter about his war experiences, and his willingness to share them. I can also remember him driving around Seattle in his cool Morgan with his old army jacket, long hair, big mustache, and one of those Scottish-looking hats that snap in the front." Joe is a graphic designer who was interested to know about Grady's art career. I couldn't give him a single website that features Grady's art, much of which was done for newspapers. But I did share with him the Route of the Hiawatha interpretive signs, which Grady created for the U.S. Forest Service and considered a major achievement. And there are his Vietnam artworks included in the book, which are in the National Veterans Art Museum. Some of them are shown on the museum website. Grady -- who never lost his affection for SPAM -- would've been beside himself with delight to hear from Joe.  Jack Hawkins, aka "Hawk," at left with crew in 1969 Jack Hawkins, aka "Hawk," at left with crew in 1969 By Julie Titone Who, exactly, was Hawk, the helicopter pilot featured in Grady Myers's Boocoo Dinky Dow cover illustration and mentioned several times in his memoir? Grady never knew, and after he died in 2011 Hawk's real name remained a mystery to me. Now I know. And I know that the face Grady portrayed in the chopper window wasn't actually Hawk, who never wore a white scarf. Enlightenment came after I inquired of folks on a few Vietnam War-related Facebook pages if anyone knew Hawk. Within hours, I was on the phone with Jack Hawkins who had emailed me to say: "I was a 'slick' pilot in the 119th Assault Helicopter Company from August 1968 to August 1969. My nickname was Hawk. Time has erased a lot of memories, but I still remember some of the 'interesting' days. I am sorry to hear about Grady’s passing, as I would like to hear what he remembered during that period. The 119th was a good company and we always tried to give the guys on the ground the best support that we could." A slick pilot was a utility pilot -- someone assigned to provide transport of troops on and off the battlefields, and to bring in supplies and ammunition. In the picture shown here, Jack is at left. A handsome Texas Panhandle rancher, his weight was down some 20 pounds from the stress and exhaustion of the job. And he did see flying as his first real job -- the first one he was trained for. "I was in college and I was actually making the grades. But I knew the draft board was not going to let me go, and I always wanted to fly. So I enlisted to go to flight school." A year later, his boots were on the red soil of Vietnam. A really rough month Jack's photo shows him standing at his Huey with, from left, crew chief Robert Legasey and a 119th gunship pilot, Jim McDonald. Gunner John Morrison is in back, cleaning his M-16. The aviators are preparing to go into the Plei Trap Valley, where Grady was badly wounded in a firefight on March 5, 1969. Before he was rescued, Grady saw a Loach helicopter come into sight, then fly away. That might have been a 4th Infantry gunship, Jack said. In any event, from Grady's painful perspective, the cavalry had not yet arrived. "I am pretty sure that it was Ski that made the tactical emergency drop of ammunition that day when Grady was wounded," said Jack. "There was a heck of a firefight going on and they were running low on ammunition. Ski’s pilot was hit during that drop. Nilius, Hud, One-Cent, Clem, and others were also there for the guys on the ground. And the gunships that gave us cover so we had a chance to get in and out." "It took a team effort and I can’t emphasize enough that we were there for one another," he added. "The real warriors were the 18- and 19-year-old kids on the ground living in pure hell. God bless them." That was a really tough month for the 4th Infantry Division, Jack said. The worst came on March 30. "We had nine aircraft shot up. I think it was Alpha and Charlie company that we pulled out ... I didn’t see how we would come out of that alive." Jack's helicopter was never shot down, "and I never took that many rounds." He was grateful to sleep each night in a bunk, however short that slumber might be. There was no such luxury for the infantry. Life was especially hard for troops in the remote and mountainous Central Highlands. "Those poor guys, they went in two directions, straight up and straight down. We called them grunts," Jack told me. "Their tour on the ground there ... I don’t think anybody that had not done that could really understand." The best part of his job in Vietnam was transporting men out of that misery.  Coming out of it alive After his year in country, Jack went back to college and got a forestry degree. But he ended up spending his career flying helicopters for the petroleum industry. For the last 17 years before he retired, he managed helicopter transport for the National Science Foundation in Antarctica. Can you get further from Vietnam than that? Now living in a small Kansas town with his wife, Ann -- they married shortly after he left the Army -- Jack said he has no regrets about his service in Vietnam. "I never talked about it for years and years. Most people can’t really understand it. Then I started going to Vietnam Helicopters Pilots Association meetings. The first one I went to was in '85 or '86. We let our hair down a little bit. We still had hair then. That was a great healing process for me." Regarding hair ... Grady remembered Hawk as bald. A case of mistaken identity? "Major Carey, our company commander, flew with me a time or two as pilot and he was bald," said Jack, who had plenty of hair in 'Nam. "He was a good commander that all of us had a lot of respect for." Just as Grady portrayed it, the aircraft commander was piloting from the left, something unusual but done in the 119th because it provided better line of sight, Jack explained. Grady did take artistic license when he drew "Hawk" on the door. The white scarf? Two of the Loach gunship pilots wore scarves, according to Bob Robbins, who also served in Charlie Company and was there at Plei Trap. So, Grady's drawing represents a composite memory. It was Hawk's helicopter that flew Grady to his first combat assignment on a godforsaken hilltop. It was Hawk who Grady thought he saw circling overhead when he lay looking up through the trees, losing blood and hope. Many children of Vietnam veterans -- including the son Grady and I eventually had -- owe their existence to pilots like Jack Hawkins who ferried their fathers to safety. With special thanks to the folks at Vietnam War History Org, Vietnam War Book and Film Club and Vietnam Reflections Through Their Eyes  By Julie Titone In the 1990s, after Grady and I had produced a first draft of Boocoo Dinky Dow, I received the most wonderful letter from Zack, the talented husband of a journalist friend. When I'd learned he was a Vietnam vet who served in the 9th Infantry Division (Grady was in the 4th), I had sent him a manuscript. I was touched and encouraged by his response. Here is part of Zack's letter. "What I think is so important about what you've done is that you've made it possible for a person to tell his story who would otherwise never have told it. Most often, when a soldier tells a story about war, it's a soldier who is or will be a writer. For example, 'The Naked and the Dead' by Norman Mailer, 'Catch 22' by Joseph Heller, etc. Or it's a writer/reporter who, although not a soldier, is at the war in some capacity. Michael Herr, a reporter for Esquire, Rolling Stone and Ramparts, wrote 'Dispatches.' Hemingway wrote 'For Whom the Bell Tolls' after being in the Ambulance Corps. But it's unusual that an ordinary soldier who is not a writer can tell his own story. "I thought the ambush scene where Grady gets wounded was particularly good. What I most liked about it was there's no sense of orientation. It's an incredible kind of chaos -- which I think is very close to the truth. and some of the details -- the way Grady sees three little red marks suddenly appear on the back of the solder standing above him -- I don't think could be invented by the best writer in the world." Zack was never able to meet Grady, but told me how much he wished he could. Our readers regularly say that, and it's the highest compliment that "Boocoo Dinky Dow" receives. By Julie Titone When Grady Myers began telling me his Vietnam War stories back in the late 1970s, the dark humor fascinated me. So did the world of the U.S. Army in a combat zone, and all of the people who populated it. As Grady described the men with whom he served, it struck me that they were not just people he never would have met, but kinds of people he never would have met, if he hadn't marched down to the Boise draft board in 1968 to report that he had dropped out of college. In the shared misery of training at Fort Lewis, the shared terror and boredom of war, the shared long months of recuperation from his wounds, Grady had interesting compatriots. In Boocoo Dinky Dow, he introduces folks from Charlie Company like these: "There was the squad’s only black, Laney. He was a former parole officer from Southern California who sported a slight beard and had an affection for marijuana. There was Longest, another California doper who had a goatee and a thin moustache that tapered into a rattail on either side. He wore love beads. "There was Fisher, an old man of 26 or 27 from the hills of Tennessee ... There was Martinez, the schoolteacher from the Southwest who would share the hot salsa and chilies that came in his care packages from home. Hano, the Hawaiian surfer, would pass around canned dried squid for everyone to chew on." The diversity of those who serve in the military was the subject of a fine essay I read this week by author/veteran David Abrams, Soldiers are More Than Just Symbols. And diversity is captured beautifully in the photography of veteran combat photographer Stacey Pearsall, as reported by PBS in the feature Portraits of veterans show us what service looks like. In a way, it was diversity that united the men who served with Grady on a godforsaken hill in Vietnam. They were different in all but their zeal for staying alive, the way they watched each others' backs, and their hope that what they were doing made some kind of sense. Below: Grady Myers, center rear, brought red-headed diversity to this crew in Vietnam. His easily burned skin was a curse under the tropical sun.  By Julie Titone This powerful work by artist Grady Myers is not among those included in his memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." This Memorial Day seems a good time to share it. Perhaps the soldier he imagined when he created this survived his battlefield wounds, as Grady did. Perhaps he lived with the pain for decades, as Grady did before his death in 2011. Sadly, Grady never had a gallery exhibit of his work. But it's good to know that most of his war-related art is included in the collection of the National Veterans Art Museum.  Paul Ridley with Julie Titone, co-author of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" Paul Ridley with Julie Titone, co-author of "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War" By Julie Titone Paul Ridley was an Army explosives specialist in the Vietnam War. On patrol, he frequently walked ahead of American troops to find and disarm booby traps. He blew up bridges. He dealt with bodies by the hundreds. Paul returned to Washington State in 1969 with a chest full of medals that included the Purple Heart for combat-related wounds. He ended his 12½-year Army career as many veterans of the era did: He didn’t talk about his military service. He got divorced. He drank. “I came back extremely isolated and stressed out,” he recalls. “I was a mess.” He pulled out of the tailspin in part by clearing minefields of isolation and bureaucracy so other traumatized veterans could move on with their lives. He's been doing the volunteer work for nearly 40 years, with the help of fellow vets and his wife, Karen. Paul made a living as a bricklayer and musician, which put him in touch with a lot of vets. On job sites and in bars, he saw turmoil and chaos in their ranks. In 1977 he moved from the Seattle area north to his roots in rural Skagit County. He played bass in Karen’s uncle’s band, “making good money and living with a lot of stressed-out vets.” Some were known as trip-wire vets. They’d move into the woods and set up wires around the perimeter of their homes or camps, attaching cans as noisemakers so no one would sneak up on them, just as they did in Vietnam. They took their stress out on their families, went jobless. Many had no idea what veterans’ benefits were available. Paul and friends started the North Cascades Vietnam Veterans Rap Group, an outlet for vets to talk about their experiences. That morphed into Operation FORWARD. “I gave them the motto ‘FORWARD’ so they would look to the future instead of dwelling on all the baggage we were carrying,” Paul says. “Our creed was to help anyone, any time, any place, any way we can. We gave them a patch so they knew they belonged to something.” Paul, who had climbed the Army ranks from private to warrant officer, put his organizational skills to good use. Likewise, he used his local connections to find people who needed help. He and Karen are from Native American and pioneer families, and know people from all walks of life. “I went to people I knew who owned gas stations, businesses, bars and such; in the fishing, the logging communities; the farmers; on the reservations and the Grange halls.” The first step in helping a vet might be getting him sober, fed, housed, or helping his family. The volunteer vets learned what social services were available. They dug into their pockets to help, and Paul sometimes landed grant money. Mostly, the volunteers learned how to navigate the maze of Veterans Administration paperwork to get disability pension checks or health benefits for vets, and they helped vets keep critical appointments. Sometimes, says Karen Ridley, it’s been necessary to get veterans to rein in their anger. “We tell them to be nice to the secretary and others on the front lines who can help your cause.” PTSD: A real problem One of the handwritten testimonials to FORWARD that Paul keeps on file is this note from George, a Navy vet who found himself on a Bellingham beach with no money and no self-esteem. “I didn’t have a plan of survival and didn’t care.” He was approached by a volunteer, a tall Green Beret vet, who asked him when he’d come home from Vietnam. And when he’d last eaten.  John Titone John Titone By Julie Titone I remember it as a bedtime story, my dad recounting how he flew over Europe and looked down on a mountain lake. The reflection of the night sky was so perfect that he became disoriented. He was flying over the moon. John Titone served in the U.S. Army Air Corps as a co-pilot on a B-17. When his nine kids were young, he told us precious little about his experiences in World War II. The memories he did share were simple, like the fact that the English grew Brussels sprouts between runways. And where were those giant tin-can American bombers going when they lifted off between the vegetables, laden with deadly cargo? Before I studied history, my only clue was a map of Europe painted on Dad's leather bomber jacket. Every mission was marked on it. As co-author of a war memoir, I've thought a lot about the power of story and how it can help combat veterans. Grady Myers regaled his friends with the stories that went into our book, "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." There's not a doubt in my mind that with his humor -- sometimes dark and ironic, sometimes wise-crackling -- Grady was coping with his memories of being a machine gunner. Tell the good stuff often enough, and the kill-or-be-killed stuff loses some of its power. Yes, Grady nearly died in battle. But he survived to participate in hospital hijinks and to buy that classic Thunderbird he was lusting after. An artist, he drew engaging pictures of his time as a reluctant but able warrior. Among his works that have been displayed at the National Veterans Art Museum, a whimsical one featuring a monkey was a crowd-pleaser. We all need comic relief. Almost every vet's experience includes good stuff: adventure, friendships, confidence-building, pride. "In many ways, that year was very exciting," says a friend who suffers from war-related stress 50 years after he was in Vietnam. "We were young, in great physical condition and full of piss and vinegar. We were in a very beautiful and exotic land with a culture none of us could have imagined. And we did things we would never tell our mothers, and survived. Even the real bad times had a positive edge because you never feel more alive than when you are close to death." Another friend told me his Vietnam service was the best year of his life. He might have exaggerated, but I don't think by much. His eyes glowed when he talked about the problem-solving involved with being a Marine mechanic in a combat zone. "It was something new every day. Every day." He came back in one piece but had a close brush with death-by-military-vehicle. It's a story he tells with relish, probably because no one else died, either.  Basic training humor, Grady style Basic training humor, Grady style I'm writing this on Veterans Day. I can't think of a better gift for people who has served in the military, in combat or not, than to let them know you'd like to hear their stories. Just open a space in the conversation. Did anything funny happen to you? Any buddies you'd like to see again? Whatever happened to those pictures you brought back? My father has outlived his bomber jacket, which was loved a bit too much by one of his sons. When asked, Dad will recall his time in the service. He told me how he fell off an airplane wing during training and broke his thumb, which delayed his deployment (I may well owe my existence to that accident). And how sick he got on the heaving troop ship that brought him back to the States. With the war in Europe over, he expected to be sent to the Pacific. The Japanese surrendered before that happened (I may owe my existence to that, too). Grady was telling stories up until his death in 2011. Even the serious war episodes, as he told them, didn't feel like a burden to listeners. I think the smiles of his audience brought some measure of peace to his good heart.  By Julie Titone No disrespect to the folks who were moved by it, but I had to click off the TV about 10 minutes into Sunday's Memorial Day concert from the National Mall. The overly groomed singers belting out patriotic songs clashed mightily with the complex, unscripted emotions I have confronted in conversations about battlefield sacrifice and its aftermath. I've had many such talks during the last few years of sharing the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." What did move me this Memorial Day were commemorations that arrived in my email box in the form of unpublished writing by two Army veterans, Michael Simpson and Carroll McInroe. I was honored to read their work. It made me think not only of those who died in the service, but also what died inside many of those who made it home. 'I had to lay down my soul' Michael Simpson, who served in Vietnam in 1967, sent chapters from a memoir so powerful I had to stop reading from time to time. In one of them he described how a Vietnamese boy, who sold Coca-Cola to the troops, stepped on an anti-personnel mine that had been planted under a tree. The blast vaporized him from the waist down and flung his upper body into a road, right where a convoy was headed. The platoon leader yelled for someone to move the corpse. When none of the other stunned soldiers responded, Michael stepped forward to do what should have been a gut-wrenching task. He writes: "This had been a kid I had known and liked, a bright, curious boy, and as I felt his hair between my fingers and dragged his dead body through the dust, I was dead inside. This is what bothers me. I felt nothing. Even to this day, as I write this, I find it troubling that when I cry at the memory, I am not grieving for this boy and the loss of his life; I am grieving for the loss of humanity within me. When this child died, and I performed this small service for my country, an insignificant thing really, drag a light object a few feet out of the road, I had to lay down my soul to pick up his head in my hand." Post-traumatic stress disorder? For decades, that wasn't something Michael thought had anything to do with him. Not even when he pushed away memories of holding a fellow soldier who died in his arms, intestines spilling out on them both, a medic nowhere in sight. Not even when his life was falling repeatedly apart. Michael is a Veterans Justice Outreach volunteer in Lewiston, Idaho. He also serves as mentor coordinator for Veterans Treatment Court. He plans to publish his book, in hopes it will help parents understand what their children could face if they go into the military. Its working title is "The Road from Happy Valley: A Pacifist's Viet Nam Experience." 'Backhoes biting holes in the earth, day after day' Texas-born Carroll McInroe served during the Vietnam era and went on to a career in the Veterans Administration where, he said, "we knew PTSD before PTSD had a name." He lives in Spokane, Washington. He wrote the following essay, titled "Waco V.A.," in the 1970s. As I entered the V.A. hospital ward, I saw my old classmates, Catfish, Gary, Ross, Richard and Avis. I saw our former Commander-in-Chief, President Richard Nixon. We soldiers did not like him much, you know. I saw Walter Cronkite telling us why and later why not. I saw long lines of teenagers being inoculated and indoctrinated. I saw the distant stares of boys fresh from battle, as we ferried them from the airport to the barracks – a hot meal, a warm bed at last. I saw the anguish, the guilt, the confusion on the faces of hundreds of other boys, as they formed yet another line to give blood, month after solemn month, for their young comrades-in-arms over 10,000 miles away. I saw backhoes biting holes in the earth, day after day, for American teenagers who no longer bled. I saw other teenagers, privileged confident ones, taunting Gold Star mothers at the gravesides of their sons. “Baby killer” was the common phrase. “Killed in Action” read the letter. “From a grateful nation,” said the flag. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, names on a wall. I saw hallways and drill fields, filled with young enlisted men, enraged over the killings at Kent State. It was 1970. I saw the same halls and fields filled with shouting senior NCO’s, demanding obedience, screaming “the college kids got what they deserved,” threatening courts-martial for any young G.I. rebel who disagreed. I saw an old friend rolling a joint with shiny metal hooks where his hands had once been. He had continued to man his M-60 as his arms were literally shot to pieces by NVA rifle fire. “I had to keep shooting or we were done. Those little people, they never quit.” The girls sat mesmerized, stoned, silent, wondering what had happened to this good young man. His girlfriend had walked out of his life because he was a war-monger. The local police were scouring the streets for him because he was “involved with drugs”; former friends and family shunned him. “Dirty long hair, bunch a’ bums.” He took a deep toke and told me, “I have nowhere to go – prison I suppose.” We spent the evening, getting high, talking, listening to Jethro Tull. I don’t know where this friend is anymore. I don’t know much of anything anymore. I know where Cat, Gary, Ross, Richard and Avis are. Their families leave a small flag at their grave sites once a year. Now listen carefully, you rare few. My classmates survived the Vietnam war. It was the homecoming that killed them. |

Julie Titone is co-author of the Grady Myers memoir "Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War." Grady was an M-60 machine gunner in The U.S. Army's Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Regiment, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. Thoughts, comments? Send Julie an email. Archives

November 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed